The academic and professional worlds are in the midst of a quiet revolution, one powered by the astonishing capabilities of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. These tools can draft emails, generate reports, and, yes, write essays with a fluency that was once uniquely human. This proliferation has sparked an equally intense technological counter-movement: the development of Detecting AI Writing detectors. As students and professionals alike find their work scrutinized by these tools, a common and often anxious question arises in search bars and forums across the internet: why is my essay detected for AI? The answer lies at the complex intersection of linguistics, computer science, and an evolving understanding of what makes writing “human.” This exploration delves into the current state of AI detection technology, its formidable challenges, and the ethical frontier we are now navigating.

The Mechanics of the Detector: Seeking the Digital Fingerprint

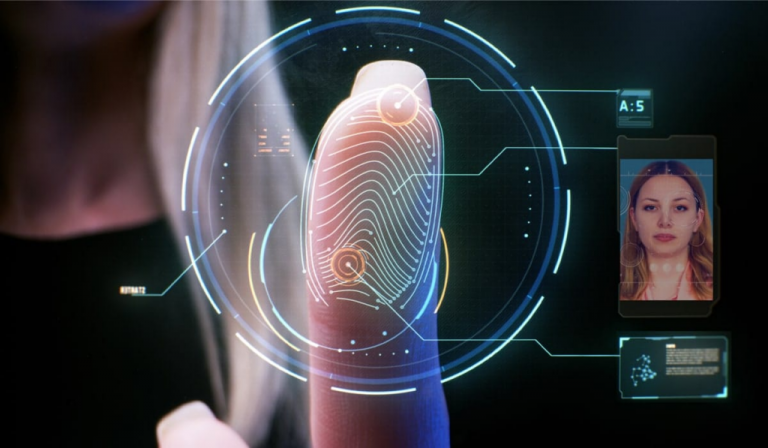

At their core, AI detectors are not searching for perfect grammar or profound ideas. Instead, they are statistical forensic tools. They operate on the principle that LLMs, trained on colossal datasets of human text, develop predictable patterns. Human writing is often messy, intuitive, and idiosyncratic. We use uneven sentence lengths, inject personal anecdotes, make subtle grammatical quirks, and vary our word choice in ways that are not always statistically optimal. LLMs, conversely, tend to generate text that is “perplexity”-optimized. Perplexity, in this context, measures how predictable a piece of text is. AI writing often exhibits lower perplexity, meaning the word choices are more common and expected given the preceding context.

Furthermore, detectors analyze “burstiness,” which looks at the variation in sentence structure and length. Human writing tends to have high burstiness—a mix of long, complex sentences and short, punchy ones. AI-generated text can often be more uniform. Early detectors also looked for a lack of specific, verifiable details or a certain “generic” tone. These tools, like Turnitin’s AI writing indicator or GPTZero, use machine learning models trained on millions of samples of both human and AI text, teaching the algorithm to spot these statistical shadows.

The Cracks in the Foundation: Why Detection is an Inherently Flawed Pursuit

Despite their sophisticated underpinnings, AI detectors are notoriously unreliable. The fundamental reason is that the goalposts are constantly moving. As LLMs become more advanced, they are explicitly trained to mimic human writing patterns, including higher perplexity and burstiness. Models like GPT-4 are far better at injecting apparent “human-like” randomness than their predecessors. This creates a vicious cycle: detectors are trained on older AI text, but are then deployed against newer, more human-like generations, leading to false negatives (AI text that passes as human) and, more problematically, false positives.

False positives are the most significant ethical failing of current detection technology. Innocent writers find themselves under suspicion, forced to prove their own originality. This happens for several reasons. Non-native English speakers, or writers with a very formal, structured style, often produce text with lower perplexity, which can trigger a false flag. Similarly, a student who meticulously revises their essay to smooth out awkward phrasing might inadvertently be optimizing for the same statistical “perfection” that an AI generates. This is a primary reason a bewildered student might search, why is my essay detected for AI, when the work is authentically their own. The psychological and academic consequences of such a misjudgment can be severe, undermining trust and creating a presumption of guilt.

Moreover, the rise of “humanizing” tools and simple paraphrasing techniques can easily bypass many detectors. If an AI generates a draft and a user then rewrites it in their own voice, the statistical fingerprint becomes muddled. This cat-and-mouse game suggests that perfect detection is a mirage. We are not detecting “AI-ness” as a fixed property, but rather a set of stylistic patterns that are rapidly converging with human expression.

Beyond the Binary: The Ethical Quagmire and Shifting Paradigms

The technical challenges point to a deeper philosophical and ethical dilemma. What, precisely, are we trying to detect? Is it the use of an AI tool, or the absence of human intellectual effort? The lines are blurring. Is using an AI to brainstorm ideas cheating? What about using it to fix grammar, or to restructure a paragraph? The tool is increasingly integrated into the writing process, making a simple binary detection not only technically flawed but conceptually inadequate.

This reality is pushing institutions away from purely punitive policing and towards a reevaluation of how we teach and assess writing. The focus may need to shift from the final product to the process. Emphasizing drafts, annotated bibliographies, in-class writing, and oral defenses of work can assess understanding in ways a detector never could. The goal becomes evaluating the student’s critical engagement with the material, rather than attempting to forensically audit the origin of every sentence.

This new paradigm acknowledges that AI is a tool that will be part of the future workplace and intellectual life. The challenge is teaching responsible and critical use, much like we taught students how to use the internet or calculators effectively. The question educators must ask is not “Was AI used?” but “Did the student achieve the learning objective and demonstrate original thought?

The Road Ahead: Coexistence Over Detection

So, how far can the technology go? In the short term, detectors will likely become more nuanced, perhaps moving from a “likely AI” score to a more complex profile of a document’s characteristics. They may be used as a risk flag for further review by a human, rather than as an automated judge. However, their ceiling is limited by the very nature of LLMs’ evolution. The ultimate “undetectable AI” is one that perfectly replicates human writing, and we are on a fast track toward that reality.

The more sustainable future lies in adaptation and transparency. This includes developing institutional policies that clearly define acceptable AI use. It also points to a potential market for immutable digital provenance tools—think of a “record of creation” that logs the drafting process in a verified way. Most importantly, it requires fostering a culture of academic integrity that is resilient to technological change.

For the individual writer caught in this transition, the confusion is understandable. If you find yourself genuinely wondering, why is my essay detected for AI, it is likely a symptom of this imperfect technological moment. It may be a stylistic coincidence, a limitation of the detector, or a sign that your writing process, even if entirely human, has inadvertently aligned with patterns the tool mistakenly deems artificial.

Conclusion

The race between AI writing and AI detection is not a winnable war for the detectors. Technology is pushing us toward a new equilibrium. The enduring solution will not be a more sophisticated digital snitch, but a fundamental rethinking of how we value, teach, and verify human creativity and critical thinking in a world where the line between human and machine-generated text is becoming increasingly, and perhaps permanently, blurred. The metric of success will shift from catching AI to cultivating uniquely human insight that no model can replicate.